Othello

A Jimi Hendrix Experience of the Moor

BBC TV/Time-Life (1981)

Produced and directed by Jonathan Miller. Anthony Hopkins, Bob Hoskins, Penelope Wilton, Rosemary Leach, David Yelland, Anthony Pedley, Geoffrey Chater.

Cyprus, sequestration, spleen-spewing commentators, domestic abuse played out in public: Watching Othello is like watching Fox News. Watching the BBC TV/Time-Life version of the play ramps up that simile as this production seems to have sprung from creatively stunted minds with warped views of history, race, and popular culture. However, what this version of Othello suffers most is the misfortune of being an establishment-branded product coming out of England in 1981, happenstances that result in the most bizarre depiction of the Moor you might ever see.

Cyprus, sequestration, spleen-spewing commentators, domestic abuse played out in public: Watching Othello is like watching Fox News. Watching the BBC TV/Time-Life version of the play ramps up that simile as this production seems to have sprung from creatively stunted minds with warped views of history, race, and popular culture. However, what this version of Othello suffers most is the misfortune of being an establishment-branded product coming out of England in 1981, happenstances that result in the most bizarre depiction of the Moor you might ever see.

Casting Anthony Hopkins in the lead role is, in itself, not a bad thing. I have no qualms with a white man playing the Moor. If men and women of color can play any of Shakespeare's characters, WASPs should be allowed the same access to Othello and Aaron. The problem in this casting, however, is timing. When the BBC set out in the mid-1970s to produce the entire Shakespeare canon, it strove for purity—or, at least, its perception of purity. This manifested on the screen as plays had to be presented in Renaissance or historical costume, and it factored into decisions behind the scenes, too. Only British actors were cast, and in 1981 the Shakespearean acting community in Great Britain had yet to develop a Hugh Quarshie or Ben Kingsley. (A popular British TV star and member of the Royal Shakespeare Company—who, in fact, appeared in one of the BBC Shakespeare productions—complained to me privately in 1980 that this restriction, brought about by Actor's Guild contracts, meant that one of the world's greatest black Shakespeareans, James Earl Jones, could not play Othello in a series purporting to put Shakespeare's best foot forward).

Instead, we get Hopkins, who can be a great Shakespearean actor (I've seen his Antony at the National Theatre, one of my five all-time favorite Shakespeareances). He can also wreak havoc on a Shakespearean text (I've seen his Lear at the National Theatre, one of my five all-time worst Shakespeareances), and he does so here. In 1981 he was between the young-actor-getting-started phase and the meticulously-prepared-mature-actor triumphs, so his Othello is pushing envelopes that don't even exist. At first he speaks the Moor's lines as if English is his second language. Othello's lovely verse, then, is given a stilted delivery; I've heard untrained high school students speak better Shakespeare. Once jealousy takes hold of him, his verse-speaking resembles a Pekingese puppy grappling with a bedroom slipper. Whole passages are delivered as guttural growls. Even his eyes bulge out as he murders Desdemona.

Hopkins' physical appearance is equally disconcerting. His skin tone changes from scene to scene. Before the Venetian council, he's lighter than even Brabantio; when he enters Desdemona's bedroom chamber in Cyprus after striking her, he looks like Al Jolson in blackface. His Renaissance knight costume has large silver stripes angling from his thighs over his hip, metal points hanging down his waist, and a giant codpiece that could contain three Dirk Digglers. The overall effect is to give him a pear shape, like Tweedle Dee, a physical demeanor enhanced by his tendency to posture himself as an insecure, stoop-shouldered little boy (I'm not visualizing Hopkins' Moor smiting any Anthropophagi or malignant and turban'd Turks). Yet, the wildest physical attribute of this Othello is his Jimi Hendrix hair. It's as if director Jonathan Miller recalled the English 1960s pop culture of his formative years and settled on Hendrix as representative of a visual depiction of a black man. I admit this could be an apt comparison of an alien black man using his incredible skills to ascend the heights of the resident white society. However, the potential of such a visual imagery is lost when you dress everybody as circa-1600 knights, lords, and ladies and your black man is really a blue-eyed, white Welshman.

Hopkins does give us one, insightfully searing moment that comes close to justifying this miscasting. At the play's key turning point, after Desdemona has made her first request on behalf of Cassio and before Iago begins working on his psyche, Hopkins' Othello watches his wife depart, saying to himself, "Excellent wretch. Perdition catch my soul, but I do love thee! And when I love thee not, chaos is come again," and the camera holds on Hopkins' eyes as they go someplace deep within. This might seem to be just another of the play's many premonitions and ironic statements, but this one looks into the past as Hopkins' eyes emphasize again as the key word in this line. This Othello has already experienced chaos, and he's not sure he can go there again.

Bob Hoskins shows much promise as Iago. He brings his cockney attitude to the part, an everyman soldier who is, himself, somewhat alien in the world of Venetian social manners. While this sets him apart from the two gulls he works upon, Cassio (played ultraseriously and solemnly by David Yelland) and Roderigo (a delightful Anthony Pedley as the consummate courtier completely unattached to reality), Iago actually shares a comfort zone with the play's other professional, battle-tested soldier, Othello. It's easy to see how the general and his ancient have a ready trust between them. This is what allows Iago to spin his web. Though we can't always understand what Hopkins is saying, watching Hoskin's Iago work Othello is this production's chief redeeming value. Anybody who believes Othello is too gullible can see in this performance how the context of their relationship and the brilliant way Shakespeare has Iago work his way into Othello's head can lead to the otherwise intelligent Moor becoming easily susceptible to the mere insinuation that his wife might be cheating on him.

Hoskins plays Iago's villainy from the start. "I follow him to serve my turn upon him," he tells Roderigo in the opening scene, and later in the same passage, "I am not what I am" (one would think Roderigo should have paid more attention to that line). What this Iago does not do is make us, the audience, complicit in his villainy. Hoskins does not deliver his soliloquies to the camera. Rather, the camera pulls in tight on him as he meditates out loud, eyes shifting about, hand massaging chin, and chuckling over every idea, thought, and observation. In the opening scene, he and Roderigo treat the waking of Brabantio (Geoffrey Chater) as a big joke, laughing all the while. This turns out to be a forecast of the Iago to come: Hoskins laughs at everything to the degree of annoyance. During the Roderigo-Cassio fight at the end, in the poorly lit, indistinguishable action and overlapping cries and yelps, the only thing we can make out for certain is Iago's laughing. The play ends with Iago's laughter echoing down an empty hall. If any of this is meant to create a connection with the audience, it backfires; we regard Hoskin's Iago as Venetian trailer trash and an intolerable jerk.

He, therefore, comes across as the play's most foolish character, albeit a dangerous fool. Iago suspects Othello of having an affair with his wife, Emilia, but in the same breath he admits he has no evidence. Nevertheless, he'll use the assumption alone as fodder for his hate, and in a subsequent soliloquy the supposed affair has become established fact. Hoskins' Iago reminds me of talk radio hosts for political and sports shows, who spout venom via baseless evidence that is nothing more than wishful thinking or personal agendas born of their own narrow, self-serving perspectives.

Penelope Wilton plays Desdemona with much self-determination and self-awareness. She knows when to appear strong even when she's worried or afraid. She doesn't blanch before her father, and then is genuinely disappointed when he doesn't offer even acknowledgement of her presence upon their farewell. Upon her arrival at Cyprus, she mingles whispered confidences and public discourse with Iago, then does the same with Cassio; only Iago doesn't see that the interactions between Desdemona and Cassio are no different than what had just passed between Desdemona and himself. When Cassio makes his first suit to her, Desdemona maintains a physical distance and a formal demeanor, even seeming to rush the conversation to a close; she knows her husband has cashiered the lieutenant, and it wouldn't be proper for the commander's wife to publicly undermine his leadership status in any way. This sense of duty—even when she has a bruised cheek and, later, has been strangled—she maintains to the very end.

Emilia's behavior is not so consistent, but that allows her to provide an emotional crux to this production. As played by Rosemary Leach, Emilia desires to please her husband (who maintains an aloof manner with his wife, but is not abusive), and thus she hands over the handkerchief. Notably, she is still pondering whether or not to do so when Iago comes upon her, at which point she stumbles into the wrong decision as heart's need shoves aside common sense. However, when Othello later lectures Desdemona on the importance of that handkerchief, the camera allows us to see Emilia watching, intently, in the background. Here would have been her moment to step forward and say, "Sir, I found the handkerchief and handed it over to Iago." But she doesn't. Whether you know what's to come or not, her silence in this scene and her lack of action afterward hit hard.

Brabantio comes off as simply silly in the opening scene, and perhaps his whole portrayal was supposed to be comical. However, Chater's ability with Brabantio's verse can't help but make Desdemona's dad seem dignified in the council scene, and his quibbling over the Duke's language carry the gravity of truth. We end up feeling sorry for this man whose daughter has eloped with a distracted-speaking, wild-haired, socially naíve manchild.

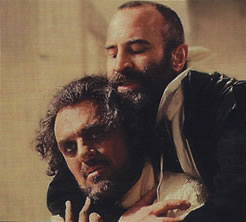

Iago (Bob Hoskins) swears fealty to Othello (Anthony Hopkins) in the 1981 BBC production of Othello. Photo from DVD package.

By the time he took over as producer of the BBC Shakespeare series in 1980, Miller had established himself as one of the world's great directors of opera. He has a visual eye that, Hopkins' Othello excepted, makes for a lovely look in this production, as many scenes resemble a Vermeer or Rembrandt painting. But his operatic touch otherwise burdens his direction of this play. Hoskins aside, the verse is given highly formal readings that even I had trouble understanding. Scenes are static, and no attempt has been made to expand the setting. Once on Cyprus, everything except the final attack on Cassio takes place in a great room of the governor's palace and the adjoining bedroom where Othello and Desdemona reside and die. The ships somehow disembark down the hall. Cassio's brawl with Montano (Tony Steedman, who expertly raises this small part to a portrayal of steady dignity) happens in this room, and Bianca (Wendy Morgan as a young, silly upper-crust society girl) suddenly appears from off camera to accost Cassio here—where did she come from, another bedroom?

Worst of all Miller drags out the action to Wagnerian lengths. The play's running time is 208 minutes; with the cuts already made in the original script (all of the Clown's scenes are missing), it could have easily clocked in at two-thirds that time. Be aware that when Othello sends Desdemona to bed for the last time, you have an hour of viewing still to go. That's just too much Iago laughing, too much Desdemona endlessly singing "willow," too much pedantic line-reading to misunderstand, and too, too much Hopkins' Othello at his worst.

Oh, I mentioned sequestration atop this review. So does Iago. Regarding Desdemona's wedding to Othello, he tells Roderigo, "It was a violent commencement, and thou shalt see an answerable sequestration. Put but money in thy purse." That Shakespeare was prescient, wasn't he?

Eric Minton

March 27, 2013

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances