The Comedy of Errors

Edwardian Order for a Comedy of Disorder

Hudson Warehouse, Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial, New York, N.Y.

Friday,

June 8, 2012 (Bottom step, right side)

Directed by Susane Lee

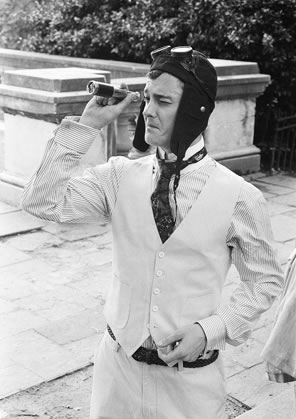

George K. Wells as Antipholus of Syracuse in Hudson Warehouse's Comedy of Errors. Photo byJoseph Hamel, Hudson Warehouse.

When it comes to productions of The Comedy of Errors, directors of late have used the play’s Ephesus setting and manic plot to environ the action in mystical exoticism, absurd surrealism, or zany cartoonism. Susane Lee took an opposite approach, setting her Hudson Warehouse production of the play in one of the most orderly time periods imaginable, the late Edwardian era of cravats, parasols, and manservants. Think Dromio of Downton Abbey.

But on another level, the orderliness of this setting contended with the disorderly setting of the theater itself, which isn’t really a theater in the traditional sense but the steps and veranda of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in New York’s Riverside Park. Audiences sit on the 1902 monument’s steps or the veranda’s marble benches and walls, and the whole is playing space, too. Dromio of Ephesus escaped a beating by clambering over the wall to one side and appeared with his rope climbing over the wall at the far end of the plaza. Dromio of Syracuse and Nell kept the gate of the Phoenix from somewhere up on the monument’s steps behind the audience, while Antipholus and Dromio of Ephesus railed on the public sidewalk in front of the audience.

That sidewalk between the steps and veranda is a public pathway and so remains open for people to traverse during performances. Actors have been known to give their speeches to bewildered pedestrians and indifferent dogs. While the Hudson River flows by peacefully down the hill from the monument, the site has all the aural ambiance of the city; actors must project in contention with helicopters flying overhead and sirens passing down Riverside Drive.

It is, however, a wonderful space to experience Shakespeare, especially Edwardian Shakespeare. How perfect when sisters Adriana and Luciana come strolling down that path in lace-trimmed, ankle-skimming day dresses, wearing gloves and carrying parasols (despite the 1902 locale, this costuming was particular to this production; Hudson Warehouse’s recent production of Romeo and Juliet was set in Afghanistan, with the Montagues as American soldiers and the Capulets as Afghans). Costume designer Emily Rose Parman built these beautiful dresses and outfitted the entire company in studied topical wear, from Egeon’s pith helmet, khaki shorts, and knee socks to the two Dromios’ butler suits.

Still, what truly makes this a fun space to experience Shakespeare is the quality of the company performing it, led in this production by George K. Wells as Antipholus of Syracuse and his Dromio, played by Peter Nash Miller. Wells’ Antipholus first appears in leather helmet, goggles, and scarf as if he’d just landed his biplane, and Miller’s Dromio is his chauffer. They play at imaginary gun battles and slo-mo saber duels and display a real brother-like companionship based on Antipholus’ descriptions of Dromio as “a trusty villain, sir, that very oft … lightens my humor with his merry jests.” Wells slips into his role like a hand in a glove, smoothly speaking Shakespeare’s verse and exuding a natural debonair charm. His Antipholus is a young man seeking adventure and delight, and though he is often disconcerted by the strange encounters he experiences in Ephesus, he is just as intrigued by the possibilities they hold.

Antipholus of Ephesus (Joe Zachary) and his Dromio (Nick Baldock) are the opposite in demeanor to the Syracusan pair: tightly wound, exhibiting persecution complexes, and functioning in a clearly demarcated master-servant relationship. Even in his first appearance, Baldock’s Dromio behaves like a whipped dog, afraid to be in Antipholus’ company or return to the wrath of Adriana. Zachary’s Antipholus is such a bully even the Duke cowers at his berating. This is a trend I’ve been noticing recently in Antipholus portrayals, with each Ephesian brother more ill-tempered than that of the previous production; I expect the next Comedy of Errors I see to play Antipholus of Ephesus with borderline personality disorder, and the one after that as a psychopath. I hope we can reverse this trend: Antipholus’ bullying nature might be grounded in Shakespeare’s text, but such portrayals run the risk of distancing themselves too much from the laughs inherent in Shakespeare’s plot. Furthermore, is the bullying personality really justified even by the text? Remember that the first time we see Antipholus of Ephesus, he already has witnessed the confusion set in motion by his twin’s arrival (Dromio’s account of meeting him on the mart), and the bewildering circumstances he finds himself negotiating escalate immediately when he’s locked out of his house. That’s enough to frustrate Buddha.

Heather Lee Rogers presents an Adriana true to her Edwardian times. The suffragette movement was under way and women were beginning to assert their sense of dignity and rights in the first decade of the 20th century, but yet they still had to live in the socially prescribed confines of the wife’s place in a marriage, especially upper strata women further governed by class mores. Rogers’ Adriana finally has had enough when her supposed husband flies into the Abbey, and she engages in a spirited argument with the Abbess, pluckily played by Margie Catov, each literally trying to out-holier-than-thou the other.

Pinch (Perryn Pomatto) tries to perform an exorcism on Antipholus of Ephesus (Joe Zachary) as, from left, the Jailor (Jonathan Minton), the Courtezan (Sarah Doudna), and Adriana (Heather Lee Rogers) watch along with members of the audience sitting on the wall of New York City's Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Riverside Park. This Hudson Warehouse production of The Comedy of Errors used Edwardian costuming. Photo by John Yarbrough, Hudson Warehouse.

After having seen a high-strung Angelo in the National Theatre production earlier this year and thinking that was so right, here we get an ever-steady Angelo in Dennis Larkin—and it seems so right, too. Nobody is at the crux of the confusion more than Angelo; he watches Antipholus of Ephesus being locked out of his house, gives the chain to Antipholus of Syracuse, demands the money for it from—and is denied by— Antipholus of Ephesus, endures Antipholus of Syracuse denying he denied the payment, and observes Antipholus of Ephesus miscommunicate twice with his servant (who happens to be the two different Dromios). Watching Larkin’s Angelo trying to handle all this with cool reason is just as funny as seeing an Angelo break down in bewilderment. This production also takes an interesting approach to Duke Solinas, played by Roger Stude looking and behaving like a very modern admiral just stepped out of a Gilbert and Sullivan show. No law says the Duke can’t be a comic character, too, and Stude certainly has fun with him.

Which brings us to another standout performance, that of Jonathan Minton as the Jailor. Full disclosure, this is my son making his New York Shakespeare debut, but I measure the “standout” in the number of laughs he generated during the show and after-show audience buzz. Credit director Lee as much as Minton for expanding on this role. Among the 14 Comedy of Errors I now have seen, some of the funniest prominently featured the Jailor (often played as a cop; in this presentation as a London bobby) turning this ten-line role into an ever-present comic gag. Most noteworthy in my recollection is the famous Trevor Nunn musical version of Comedy of Errors for the Royal Shakespeare Company in the mid-1970s that cast Richard Griffiths, RSC’s top comedian at the time (he played Bottom that year, too), as the Jailor. Rather than playing up the underlying darkness in the play, directors would do better to exponentially enhance the play’s comedy by giving us a Jailor like Minton’s version, fumbling with handcuffs, blowing only air on his police whistle, playing the matador with a strait jacket to the frantic Dromio’s bull, and otherwise looking too confused by life in general to be confused by the mayhem that ensues when two pairs of identical twins suddenly appear in the same town.

It was also perfectly in keeping with this production’s Edwardian order for Shakespeare’s play of disorder played on this monumental 1902 stage.

Eric Minton

June 15, 2012

Special Note:

Early in this production, Antipholus and Dromio of Syracuse seem to mime a light saber duel (maybe it was supposed to be broadswords, but it had the look of a Matrix-cum-Star Wars scene). The moment was funny in and of itself, but it also offered a glimpse into a modern way of playing that particular pair of twins as geeks, especially in opposition to the more buttoned-down hometown pair of Ephesus. Dromio of Syracuse, in particular, talks in comic allegories, much of it not accessible to 21st century audiences. For example, he cannot simply say Antipholus was arrested; he lists a dozen metaphors before finally hitting on one that Adriana and Luciana understand (and, later, he does another dozen before even his master gets him). If Shakespeare wrote this play for a performance given to law students during a Christmas festival (The Comedy of Errors was at least performed for such an event in 1594), these lines were inside jokes now obtuse for a modern audience. But, then, Dungeons and Dragons and sci-fi gaming conversations are just as obtuse for modern audiences, too. It might be fun to see a production with Antipholus and Dromio as modern-day nerds ever blurring the lines between their real world and their gaming scenarios.

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances