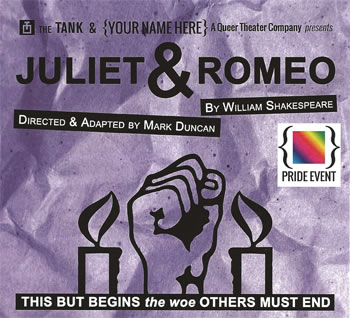

Juliet & Romeo

Lesbian Love in a World of Hate

{Your Name Here} A Queer Theater Company, The Tank, New York, N.Y.

Sunday, June 16, 2013, second row, studio theater

Directed and adapted by Mark Duncan

While William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is considered one of the greatest love stories of all time, the play is really about hate. Hate, not love, drives the plot, for without the prevailing and deadly enmity between the Capulets and Montagues, the love affair between Romeo and Juliet would not have to jump through so many hoops and ultimately come to its tragic end. Moreover, it is in the play's hate that directors find their conceptual contexts: black versus white, nouveau riche versus old money, immigrants versus natives, Jets versus Sharks, rival Mafia families, rival political families, rival corporate families, rival tribes.

While William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is considered one of the greatest love stories of all time, the play is really about hate. Hate, not love, drives the plot, for without the prevailing and deadly enmity between the Capulets and Montagues, the love affair between Romeo and Juliet would not have to jump through so many hoops and ultimately come to its tragic end. Moreover, it is in the play's hate that directors find their conceptual contexts: black versus white, nouveau riche versus old money, immigrants versus natives, Jets versus Sharks, rival Mafia families, rival political families, rival corporate families, rival tribes.

In Juliet & Romeo, the play's hate is fashioned into a spotlight on homophobia. Victoria Tucci has found in Romeo and Juliet many elements that ring true to the day-to-day lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youths. After producing Romeo & Juliet: Forbidden Love Comes to North Carolina as part of an advocacy campaign opposing an antigay marriage amendment in that state, Tucci has teamed up with {Your Name Here} A Queer Theater Company in New York to further hone the adaptation, renamed Juliet & Romeo, and significantly trimmed to a 90-minute run time. The Tank, a small studio theater just off Broadway, provided the venue.

Such a specific-theme-driven adaptation by its nature requires playing loose with Shakespeare's text, starting with the fact that Romeo is now a girl (played by Tucci), Mercutio is openly gay, and Friar Laurence becomes the Rev. Laurence, something of a Unitarian minister. I generally don't have a problem with such warping of Shakespeare, as long as it stays true to his themes and entertains or enlightens us, or both. My criticism of this production, in fact, is that it doesn't go far enough with its intent. Adapter and director Mark Duncan downplays or even ignores the varying shades of hate that Shakespeare himself offers in the text, all pertinent to the many facets of homophobia.

The production's program notes highlight three themes—"The reality of the world of our play"—explored in this modern-dress Juliet & Romeo: suicide, homelessness, and hate crime.

- Romeo's and Juliet's suicides spring from their adolescence, the psychology of which could be read (and played) in many ways, from naive romantic notions or an immature short-term perspective to a pact of true love or a noble gesture in the face of their families' hate. Turn them into a lesbian couple and you add a sense of overwhelming despair to the equation, as 30 percent of LGBT youths have reported attempts at suicide compared to 10 percent of all other adolescents, according to statistics presented without citation in the play's program.

- Lord Capulet threatens to kick Juliet out of his house if she refuses to marry the Count Paris. "Hang, beg, starve, die in the streets, for, by my soul, I'll ne'er acknowledge thee," he tells her. The program reports, again without citation, that up to 40 percent of the 1.6 million homeless children in the United States are LGBT and that more than 10 percent of transgender people have been evicted from apartments because of their gender identity.

- Hate crimes—"civil brawls"—are a fact of life in fair Verona. As the hate is between anybody associated with the Montagues and Capulets, it is a hate by association, a hate inspired by what the individual represents rather than a direct dislike of the individual himself, even if that individual is a dog. "I hate hell, all Montagues, and thee," Tybalt says, and Benvolio is antsy on a hot day while "the Capels are abroad, and if we meet we shall not scape a brawl." LGBT youths know that fear, as nearly 20 percent report being physically assaulted because of their sexual orientation, according to the program notes (again, without citation).

Duncan relies on a visual element to press the last point. Two police barricades, decorated with flowers and placards bearing gay rights slogans, are positioned about the stage according to the scene. For example, they form Juliet's balcony. At play's end, cast members emerge with candles and pictures of Mercutio, depicted as a victim of Tybalt's hate crime.

Ah, but this depiction is without citation. It's true that Tybalt (a seething Sam Kinsman) is goaded into fighting Mercutio (flamboyantly played by John Edgar Moser) when the latter taunts Tybalt with an obviously un-Shakespearean meaning to the line "Make it a word and a blow." The subsequent fight has a knife-wielding Tybalt overmatching Mercutio who uses one of his spiked-heel boots as a weapon. But Tybalt's primary motivation, even in this presentation, is to attack Romeo expressly because she is a Montague. That she is gay, Tybalt never broaches, except to remark that she "consorts" with Mercutio.

But what's Montague? The violent rivalry between the two families that is the framework of Shakespeare's play is given no context in this LGBT-focused adaptation, despite the fact that what Shakespeare writes is ripe for the purpose. Because Shakespeare never explains the root cause of the feud, directors can, and have, played it in any context that fits their purposes. We know little about the Montagues except that they have enough wealth to employ a staff of serving men. Meanwhile, we know a lot about the Capulets. They not only are wealthy, they are politically connected to Verona's prince, and Lord Capulet is notably image-conscious. He would not allow Romeo to be attacked in his house, even though the Montague crashed his party, and his anger at Juliet arises not only from his sense that the child should obey the parent but that her protestations will reflect poorly on Capulet himself after he has promised her to Paris: "A gentleman of noble parentage…and then to have a wretched puling fool, a whining maumet, in her fortune's tender, to answer 'I'll not wed, I cannot love; I am too young, I pray you pardon me'!"

It's not a stretch to see Capulet's behavior here and throughout the play applied to religious and political antigay conservatives, and a family with such an identity would naturally form great enmity toward another powerful family who has an openly gay daughter and maybe advocates for gay rights. But these Capulets show no such attitude. Lady Capulet (a steely Emily Tuckman) is a self-absorbed wealthy housewife taking more care for her toenails than her daughter's well-being. Ron Nummi is a gregarious Capulet, a delightful man until his daughter turns on him. Rather than religious or political zealotry, though, Nummi in this scene gives a rich portrait of a father, not yet emerging from the fog of grief over his nephew's murder, trying to come to terms with his little girl suddenly turned into a woman and inexplicably crossing him.

A social-political reading of the Capulets might require more script doctoring or explicit extra-textual visuals, especially with the Prologue, but a bolder homophobic portrayal on the part of the Capulets would unleash so much more potential in situations and key verses already present in the play. The opening scene would become, clearly, an attack on gays, and Samson's threat to "push Montague's men from the wall, and thrust his maids to the wall" would be loaded with a sinisterly homophobic intent. Furthermore, the fear Benvolio (Rose-Emma Lunderman) expresses about being alone with Mercutio while the Capulets are abroad would resonate more. Speaking of Mercutio, an openly gay kinsman to the Prince would cause the ultraconservative Capulet much discomfort, especially at his party (even though Mercutio's face is masked, his mannerisms are not) and reveal many new dimensions to Tybalt's killing him.

Shakespeare, in fact, delivers Tybalt as a ready-made homophobe. He claims that Romeo is at the party "to fleer and scorn at our solemnity," a conclusion he arrives at not by anything she does (though Tybalt does overhear her meditations on Juliet) but merely by being what she is, a Montague (or, in this production, openly lesbian). "I'll not endure her" Tybalt says to Capulet, and then argues of Romeo's presence in the Capulet's home "'tis a shame." But his most chilling line is this: "Now, by the stock and honor of my kin, to strike her dead I hold it not a sin." Such is the zeal of many a religious conservative that, despite the clearly stated Sixth Commandment, their own kind's "stock and honor" is all the justification they need to do violence to others who do not adhere to that particular stock and honor.

Nurse displays a different kind of religious fervor. In a sweetly comic portrayal, Martha Wollner plays Nurse with a genuine love for Juliet and a close, personal relationship with God; she is ever fingering the rosary around her neck, and she notably kisses it when Juliet expresses penance for defying Lord Capulet. Watching this struck me as a visual rendition of a statement I hear so often: "I don't have anything against gays, I just don't think they should have the right to marry." If you are willing to deny a certain class of people an equal right—legal enfranchisement—you have something against them. Period. Likewise, Nurse shows respect and genuine care for Romeo, but deep down she wishes Romeo would just disappear. Though Nurse knows that Romeo and Juliet are legally married, in her Catholic eyes they are not legitimately married, and thus her advice to Juliet after Capulet's insistence on the marriage to Paris is not, in her mind, one of advocating bigamy.

Such readings are only hinted at in Duncan's adaptation and the performances on stage. Much of the effort in his and Tucci's collaboration is to cast Romeo as a girl and turn the character's romantic anguish—over Rosaline and over Juliet—into an LGBT person's path of self-discovery, struggling to be considered a valuable human as a gay person instead of merely "fortune's fool." Scenes not directly related to this path are excised. And what about Juliet's path of self-discovery? In this adaptation, we sense she does not start the play seeing herself as gay (oh, but if she knew herself to be a lesbian, how poignant would be her considering marriage "an honor that I dream not of"). A lesbian Juliet would know the dangers of coming out of the closet in a family like the Capulets, and this fear would run rife in her trepidation at the speed with which she and Romeo enter their relationship. Her "Come night" speech then would become her own personal testament to what she is and the hopes she harbors. However, this speech is cut entirely in this production.

Yet, this production has a Juliet in Leanne Mercadante who could handle such a heavy psychological, intellectual, and emotional load. Mercadente played Juliet to Tucci's Romeo in the original North Carolina production and also played the part with the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts in Beijing, and she beautifully captures the girl on the cusp of womanhood, maneuvering the minefield of pursuing a first love with dangerous consequences. Her line readings in the balcony scene are enrapturing, and she continues to plumb the depths of Juliet's verse with crystal clarity in her morning-after scene with Romeo and her counseling session with the Rev. Laurence. These moments are so beautifully rendered that it makes cutting her "come night" speech a glaring loss. Advocacy theater is a noble enterprise, but when you have a Juliet of the caliber of Mercadante, it's worth exploiting for the value of Shakespearean entertainment alone.

To be sure, Juliet & Romeo is noble enterprise, an adaptation that serves well its role of advocating on behalf of LGBT issues. However, with a bit more maturity, it could evolve into a more resonating play that reaches across the great divide of Capulets and Montagues still hampering our society today when it comes to issues of LGBT rights. Tucci and Duncan need not look far for guidance. Shakespeare is standing by, ready if not eager to provide all the subtexts they need.

Eric Minton

June 21, 2013

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances