Julius Caesar

Et tu …?

Chesapeake Shakespeare Company, Baltimore, Maryland

Friday, October 13, 2017, B–108 &109 (center stalls)

Directed by Michael Tolaydo

Julius Caesar is dead. His assassins vibrate in the shock of their butchery. As their senses return, some shout "Liberty! Freedom! Tyranny is dead!" and others begin thinking of how to spin their deed to other senators and the public. Their leader, Brutus, inspires them to "stoop, Romans, stoop," bathe their hands in Caesar's blood, and walk to the marketplace, weapons held high, crying "Peace, freedom, and liberty!" Cassius, the conspiracy's instigator, concurs, and then excitedly shouts, "How many ages hence shall this our lofty scene be acted over in states unborn and accents yet unknown!"

Mar Antonia (Briana Manente) kneels next to the body of the just-murdered Julius Caesar (Michael P. Sullivan) in the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company's production of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. Antonia (nee, Marc Antony in Shakespeare's text) demonstrates her faux fealty with the assassins in this scene. Photo by Robert Neal Marshall, Chesapeake Shakespeare Company.

Is this a joke? Self-aware winking on the part of the playwright, you think? William Shakespeare inserted this comment at this pivotal moment of his play, The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, and though the timing might seem odd, such a joke fits in with the play's comic threads, which only emerge in the hands of Shakespeare-steeped directors and actors. However, such a director, Michael Tolaydo, in his incisively insightful direction of the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company's production of Julius Caesar, choses to squelch much of the play's humor. Vince Eisenson, a Shakespeare-steeped actor playing Cassius, speaks the "acted over" lines triumphantly, but it gets nary a laugh from the audience during the performance I witnessed.

That's because it is not a joke, not in this production, not in our endless trudge through mankind's political timelines. In this modern-dress production by actors in a state unborn at the time of Caesar's assassination (and when Shakespeare wrote this play) and speaking in an accent then unknown, Cassius is not necessarily ascribing a theatrical meaning to his statement (after all, Cassius "loves no plays"). It is the historical event portrayed here that proves redundant. The assassination of an ambitious politician by other ambitious politicians ostensibly to free their nation of tyranny only to replace it with their own version of tyranny would be enacted repeatedly since Caesar fell in 44 BC. Et tu, Brute? Caesar says as Brutus stabs him. Et tu, Richard? any number of Shakespeare's characters in Richard III might have said. Et tu, Booth? Et tu, Princip? Et tu, Lenin? Et tu…? Add character assassination to actual murder, and the re-enactment of Caesar's demise reaches hundredfold proportion in just this month alone.

Shakespeare's playwriting career launched with his account of England's War of the Roses, and at the time he wrote Julius Caesar, restless, coup-conspiring nobles orbited his own Queen Elizabeth. His "tragedy of Julius Caesar" (not, notably, the tragedy of the "honorable" Brutus, the actual lead character with more than a quarter of the play's lines) plays as a cautionary tale for his country. Cassius crowing that such scenes will continue to be enacted "in states unborn" might be an inside joke, but Shakespeare also is ringing a wider warning specifically beyond his own time and place. In the Elizabethan Age, legend asserted that Caesar built the Tower of London, which Shakespeare alludes to in his two Richard plays; thus, England, as a nation, was born by the time of the assassination (so says Cymbeline in his eponymous play by Shakespeare). On the other hand, there were states unborn and accents unknown in the newly discovered land then being explored across the sea.

Tolaydo runs with the wider warning of Shakespeare's prescience as integral to the guiding concept of this staging rather than relegating Cassius's line to an off-hand joke. Which begs the question: Who exactly is Caesar meant to represent in this Chesapeake Shakespeare Company production? Answer: Caesar is Caesar. Brutus is Brutus, Cassius is Cassius, Octavius is Octavia, and Antony is Mar Antonia (more on the re-gendering of key roles later). Tolaydo forbade his designers from superimposing Shakespeare's play on a recognizable head of state, political party, or current social movement (Scenic Designer Audrey Bodek built a concrete wall with a balcony and abstract railing beyond a bare stage, and Costume Designer Kristina Martin uses details in the clothes that speak volumes about the personalities wearing them but not their ideologies). As for who's who, "Let the audience decide for themselves," Tolaydo says in press notes. "The play is not really about Caesar or any particular leader: It is about trying to protect the Republic and the voices of the Roman citizens. One can argue that very notion of protecting the citizens' voices is at the heart of America's current political situation. Julius Caesar speaks of our times right now."

This production speaks most formidably in the performances of its key roles with characters that cut across political affiliation. Michael P. Sullivan's Caesar, in a white suit that bespeaks formality and casualness in the wearing of it (later in his home we see him in plaid pajamas and a gold robe), is a haughty man given to public show and demonstrative speaking. Yet, this is no mere braggart; he's politically astute, using generosity, bonhomie, and flattery as tools in a quiver that also holds military reputation, stout resolve, and volume. The person Caesar fears most is the man he acknowledges as intelligent enough to see through his multifaceted facade. "He reads much," Caesar says of Cassius. "He is a great observer, and he looks quite through the deeds of men," a quality most mortal, politically, to a showboat politician.

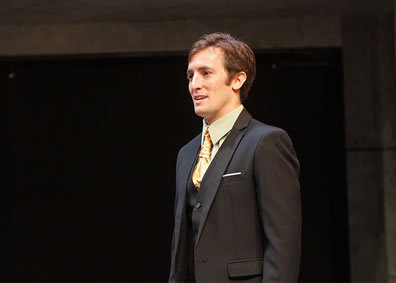

Eisenson takes Caesar's description of Cassius as his truth. Wearing a three-piece dark gray suit with green shirt, red and black patterned socks, and a gold tie tied into a multiple Van Wijk knot, Eisenson's Cassius is a volatile ball of intelligent energy. Describing how, on a dare, he jumped into the "troubled Tiber" with Caesar and ended up having to save Caesar from drowning, Cassius says, "Accoutrèd as I was, I plungèd in," and Eisenson slaps his chest as if to suggest that he would do so in that fashionable suit of his. And he would, apparently, for in the storm of the ensuing scene, he's wearing that suit, but with tie gone and shirt unbuttoned. This juncture of impetuousness crossed with careful study of human nature is where Eisenson plays Cassius, carefully laying out the means of ensnaring Brutus in the conspiracy to kill Caesar and then watching nervously as Brutus alters the plot's tenor and direction (and underestimates Antonia).

For Brutus is an honorable man—as Brutus himself will tell you frequently. Wearing a light blue suit jacket with a handkerchief in the pocket, cream pants, and striped tie, Ron Heneghan maintains a serious demeanor throughout his portrayal, with the stiff back of an Army officer and glasses that he likes to peel off his face in moments of deep meditation or pondering proclamation. After Brutus responds to Cassius's overtures with "I will consider," Eisenson gives an ironic edge to his reply, "I am glad that my weak words have struck but this much show of fire from Brutus"; Brutus nods solemnly.

The play's crux scene, Brutus's soliloquy meditating on the prospect of killing Caesar, I've never seen better played than it is in this production. Heneghan, wearing black silk pajamas and robe, establishes the markers for a Brutus who eventually displays a bigger ego than Caesar's, even referring to himself in the third person. His speech is a study on logical progression, but in Heneghan we see a Brutus merely aligning logic to a conclusion he's already reached. "To speak truth of Caesar, I have not known when his affections sway'd more than his reason. But 'tis a common proof that lowliness is young ambition's ladder whereto the climber-upward turns his face. But when he once attains the upmost round, he then unto the ladder turns his back, looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees by which he did ascend. So Caesar may." May? And moving on to the serpent's egg "which, hatched, would, as his kind, grow mischievous," Brutus determines they must kill Caesar "in the shell," assuming, of course, that he is, indeed, looking at a serpent's egg: Would that be a cobra or garter snake? I've never realized before how much Brutus operates on presumption throughout this play, and the source of his presumption is his ego. Upon reading the letter his servant Lucius (Imani Turner) finds thrown in the window, Brutus takes on the task of deciphering its obtuse sentences: "Thus must I piece it out." How like Malvolio in Twelfth Night saying of the faux letter from Olivia "If I could make that resemble something in me." Just as Maria in that play knows how to work on Malvolio's self-loving psyche, Cassius knows how to work on Brutus's. By the time we get to their Act IV argument scene in Brutus's tent—played here with violent vocal intensity that threatens to uncase in an explosive physical contention—Brutus has reached the height of his ladder and is "scorning the base degrees by which he did ascend."

For all that, Heneghan's Brutus fears much. "O conspiracy," he says with a shudder when the faction arrives at his house. At the moment of the assassination, Cassius frets over every minor detail while Brutus is the picture of calm—until the assassination actually begins. Brutus had decreed that they kill Caesar "boldly, but not wrathfully: let's carve him as a dish fit for the gods, not hew him as a carcass fit for hounds," an idealized notion that earned a disconcerted look from Cassius. Now, in the moment of murder, the rest wrathfully hew Caesar (especially Cassius) while Heneghan's Brutus freaks, running back and forth peering into the theater's voms and unable to make a single knife thrust until Caesar falls into him. Only with "Et tu, Brute?" does Brutus actually et tu.

I came into this production keen to see how re-gendering Antony and Octavius (Caitlin Carbone plays the latter as Octavia) would inform their relationship. That was man-thinking on my part. That the two characters are now women has nothing to do with their portrayals. In delivering Antonia's famous funeral oration, Manente does not present a woman manipulating the audience. Instead, it is a portrayal of her humanity reacting to the moment, to her grief, to the wavering crowd, to the reality of the Caesar she knew and now mourns. One could say this is a woman's perspective toward this speech; and if you buy into that, Mar Antonia has hoodwinked you, too, as she subsequently consolidates her power into a new tyranny.

Rather, turning two of the three triumvirs into women (Keith Snipes plays a Lepidus already wary that the other two won't treat him as an equal) throws the play's two original female roles, the noble housewives Portia (Carbone) and Calpurnia (Lesley Malin), into relief. Calpurnia shows private influence on Caesar—via begging on her knees—that vanishes immediately upon his persona going public. Portia gets on her knees before Brutus, too, but then reveals the self-inflicted wound in her thigh, illustrating her strength of resolve. Carbone's Portia has a greater spirit than the confines of being Brutus's wife allows. "Am I yourself, but, as it were, in sort or limitation, to keep with you at meals, comfort your bed, and talk to you sometimes?" she complains to Brutus after he spends the night by himself pondering the conspiracy. "Dwell I but in the suburbs of your good pleasure? If it be no more, Portia is Brutus' harlot, not his wife." In Shakespeare's London, the suburbs were the red-light district, but in modern dress, the term carries a new relevance to our ears. Carbone clearly portrays a distracted woman under the mental pressures and anxieties that will eventually break her. "I have a man's mind, but a woman's might," she says, that might being not her constitution but her social limitations.

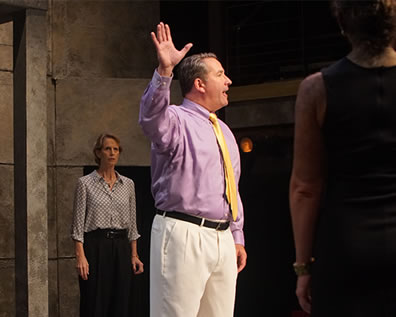

Top, Caesar (Michael P. Sullivan) addresses the senators, inlcuding the professorial cynic Casca (Mary Coy in the background), at the capitol before his assassination in the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company's production of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. Above, Cassius (Vince Eisenson) "looks quite through the deeds of men." Photos by Robert Neal Marshall, Chesapeake Shakespeare Company.

It is not gender, but generational casting that keys the interpersonal relationships in this production. Carbone's Octavia (the part almost always referred to in Shakespeare's script with the tag "young Octavius") is a Millennial, inexperienced but closely watching and learning from Antonia though already proving the smarter and more mature woman. When Octavia is certain of her course, she takes it. "Why do you cross me in this exigent?" Manente's Antonia says with seething frustration when Octavia contradicts her command. "I do not cross you," Carbone's Octavia replies with matter-of-fact confidence; "but I will do so." Earlier, Carbone's Octavia bristles when Antonia tells her, "Octavia, I have seen more days than you." Octavia's irritiation at this generational slight we'll also see in Eisenson's Millennial Cassius in the next scene. After he and Brutus have cooled down from their heated argument and rebonded in mutual admiration, they begin forming a military strategy. Cassius states his recommendation with good reasons that they stay put and let Antonia and Octavia come to them. Brutus interrupts, "Good reasons must, of force, give place to better," and Eisenson's Cassius stiffens his posture and goes vacant-eyed as Brutus presses his own preference to march toward their foe, even shutting off an attempt by Cassius at further discussion. After the argument that just passed, Cassius dare not press his point further—"Then with your will go on: We'll along ourselves and meet them at Philippi," he says resignedly—though he knows Brutus doesn't know better; Brutus just knows what he knows.

Tolaydo's detail-oriented direction results in small bits of stage action that enhance Shakespeare's script intellectually and emotionally. Turner's Lucius stops the show when he soulfully sings a soul-stirring lullaby for Brutus before falling asleep himself. Brutus tucks him in and starts reading his book before the appearance of Caesar's ghost startles him. In the crux meditation scene of the second act, when Lucius brings Brutus the letter, Brutus says, "Such instigations have been often dropped where I have took them up," pulling another letter out of his robe pocket and comparing the two. Letters in hand also come to the fore in the argument scene, first Cassius and then Brutus scrounging through the documents on Brutus's desk to find the evidence of the other's duplicity. During the faction's meeting at Brutus's house, Decius (Séamus Miller) asks, "Shall no man else be touched, but only Caesar?" whispering the name "Caesar." Popilius (Malin), who enigmatically wishes that the conspirators' "enterprise today may thrive" ends up watching the assassination unfold and, when it is done, runs out swiftly but silently.

In addition to her strong turns as Portia and Octavia, Carbone plays the pivotal role of Antonia's servant, sent to be an ambassador to the assassins immediately after the murder. This episode, excised in too many productions, evokes the palpable fear in the air via the phrases the servant uses, which Carbone delivers with nervous gestures and rapidity, immediate to appease for her own safety's sake while determined to carry out her duty on behalf of Antonia. When Antonia herself meets with the assassins and offers to shake each one's hands, Brutus is reluctant to do so until Cassius nods that he should. Having clasped each conspirator's hands and looked in their eyes, Antonia kneels by Caesar's body and bewails his death. The assassins press her for her allegiance to them, she takes out her own dagger, and a phalanx of knifepoints immediately point at her. "Friends am I with you all, and love you all," she quickly says, and then she stabs Caesar in his chest and bathes her own hands with his blood—whereupon she begs to know the reason for the assassination and requests to speak at Caesar's funeral.

The keenest detail in the staging of that funeral is the third of the four citizens shouting interjections during Brutus's and then Antonia's speeches. As Antonia has turned the crowd toward again honoring Caesar, the Third Citizen from somewhere off-stage shouts, "I fear there will a worse come in his place." How true. But Third Citizen's next interjection rings with wider irony. "There's not a nobler man in Rome than Antony."

Not only now, in our nation and with our accents, but how many ages hence shall this scene be acted over?

Eric Minton

October 26, 2017

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances