Pericles

A Quadruple-Quality Life

Fiasco Theater, Classic Stage Company’s Lynn F. Angelson Theater, New York, New York

Wednesday, February 28, 2024, B–201 (Center left for thrust stage)

Directed by Ben Steinfeld

Pentapolis's King Simonides (Andy Grotelueschen) gets wild and crazy as host of a party for his daughter in the Fiasco Theater's production of William Shakespeare's Pericles at the Classic Stage Company in New York. Playing the knights and lady circled around Simonides are, clockwise from left, Paco Tolson, Emily Young, Noah Brody, and Devin E. Haqq. Photo by Austin Ruffer.

Jacques in William Shakespeare’s As You Like It famously says “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players: …and one man in his time plays many parts”— parts meaning roles, which, theatrically, are individual persons. Turn that conceit around, and you could say many parts make up one man. As we grow older, our individual selves combine to create an increasingly complex but unified whole self that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Shakespeare addresses this redirection of Jacques’s equation with his late-career play Pericles. At least, that’s the metaphor Fiasco Theater teases out of this much-maligned play in their fascinating production at Classic Stage Company in which four men each play one part of Pericles.

Given the masterpieces the small New York City theater company has forged from Shakespeare’s other maligned plays—Cymbeline, Measure for Measure, Two Gentlemen of Verona—a Fiasco Pericles was inevitable. Pericles nevertheless remains the untamable punk of the Shakespeare canon. Co-written, scholars believe, by George Wilkins, who was something of a punk himself, Pericles breaks staging rules, ignores common sense, populates its script with more caricatures than characters, joys in bawdy pleasures with whores and horny princesses, relishes evil as much as divinity, and goes for overkill: two sea storms, two tear-inducing family reunions, one kingdom plagued by famine, another by incest.

Fiasco approaches all its Shakespeare productions with a proven formula, starting with an actor-centric and ensemble mindset. They subject each play to years of study and ensemble discussions, thoroughly mining the text for clues and patterns that turn written characters into four-or-more-dimensional humans. They find thematic strands they turn into theatrical metaphors: a trunk in Cymbeline, doors in Measure for Measure, letters in Two Gents. They weave original music into the script. All of this they prepare and present with an exceptionally high grade of acting and musical talent.

Subjecting Pericles to this drill, another ingredient crept into Fiasco’s thinking: their own life experiences. “We’ve gained partners and children; we’ve lost parents,” Director Ben Steinfeld, one of Fiasco’s three founding co-artistic directors, writes in his program notes. Recounting the fledgling company’s progress since launching in 2011 with their surprise Off-Broadway hit Cymbeline, Steinfeld describes personal revelations that emerged among the company's members while working on Pericles, originally developed in 2022 through Fiasco’s “Without a Net” initiative. “We’ve had the chance to collectively explore our understanding of grief and loss, of parenting, of the ways in which a culture is affected by its leaders, of what the divine means to us now, of which rituals have meant the most in our lives.”

As director, Steinfeld fittingly plays Gower, the 14th century English poet who wrote the narrative poem on which the play is based and comes from the grave to serve as Chorus. Steinfeld alternates speaking and singing Gower’s narration (with some textual revision) accompanying himself with original music on his guitar. Gower’s four-beat rhyming couplets are so formal that actors can get trapped in their staid structure. Steinfeld is more balladeer than zombie narrator, an inviting performance reminiscent of his fourth-wall breaking Feste in Fiasco’s 2018 production of Twelfth Night, also at Classic Stage Company.

The full-thrust stage is empty save for an old, pentagonal coffin and nine crates arranged in a circle. The backdrop is a brown gauze sheet with three doorways. Lighting Designer Mextly Couzin's deft touch makes for subtly poignant atmospheres, and during the second sea storm he reveals Pericles and his crew manning the ship's rigging behind the backdrop. Per Fiasco tradition, when not acting in a scene, cast members are visible sitting at the back of the stage contributing music or sound effects. The play starts with the cast, wearing muted ancient-world costuming by Ashley Rose Horton, singing lines based on Gower’s opening lines. They sit on the crates, using them as percussion instruments, except guitar-playing Steinfeld and original Fiasco member Paul L. Coffey playing cello. The crates will serve as seats, stands, and props throughout the play, and the coffin doubles as a rostrum.

This production’s overarching theatrical metaphor, however, is not a prop this time but a succession of actors play the 16-plus years' progression of one man's life. Along the way, the Fiasco formula creates a succession of theatrical wonderment rooted in and improving on the text.

Pericles (Paco Tolson), the prince of Tyre (modern day Lebanon), wants a wife so badly he risks his life aiming for the daughter of Antioch's king (she's played by original company member Emily Young, he by Fiasco Founding co-Artistic Director Noah Brody). The blue-sash-adorned Pericles must answer a riddle amid the severed heads of previous non-riddle-solving suitors. Other cast members with staffs standing on crates play Antioch’s guards until mention is made of suitors’ heads; thereupon these guards poke their staffs under their chins and literally play dead heads on a pole.

Pericles solves the riddle—that the king has been screwing his daughter—and flees Antiochus’s subsequent wrath. Pericles’s counselor Helicanus (Coffey, playing him as an old man), suggests Pericles sail for famine-suffering Tarsus, stealing lines that Tarsus’s King Cleon is supposed to speak in the following scene. This narrative adjustment makes more sense than the original text.

Pericles earns the undying thanks of Cleon and his wife Dionyza (Devin E. Haqq and Tatiana Wechsler, respectively), though the scene's blocking hints at how undying doesn't necessarily mean unmurdering. Cleon is looking at Dionyza when he says to Pericles, “When any shall not gratify, or pay you with unthankfulness in thought, be it our wives, our children, or ourselves, the curse of heaven and men succeed their evils!” Dionyza irritably glances away: Cleon knows of what unthankfulness she’s capable.

As Pericles sails into his play’s first fatal sea storm, the cast stretches across the stage a white cloth resembling a billowing cloud and wrap it around Pericles as if he is languishing in a wave. On the chime of a dinner bell, the role of Pericles transfers before our eyes from Tolson to Wechsler, who washes ashore in Pentapolis, lone survivor of the shipwrek.

Pentapolis fishermen (from left, Emily Young, Paul L. Coffey, and Noah Brody) meet the shipwrecked Pericles (Tatiana Wechsler) in Fiasco Theater's production of Shakespeare's Pericles at the Classic Stage Company in New York. Photo by Austin Ruffer.

Scholars generally contend Wilkins wrote the play's first half, notable for its plodding narrative and stilted language. This includes the Pentapolis scenes which nevertheless have a rich vein of comedy running through them (maybe Shakespeare tweaked them before fully taking over the play's composition with the second sea storm). Thus, the Pentapolis scenes don’t get their due when rating the Shakespeare Canon’s great comic moments. Fiasco rectifies that by judicious trimming, unearthing small but significant comic devices within these scenes, and the ensemble's acute grasp of even seemingly ubiquitous characters as the three fishermen Pericles encounters upon washing ashore. Brody, Young, and Coffey present singular performances of these genial generics.

For the knights' tournament Pericles enters wearing his armor breastplate that the fishermen found entangled in their nets, Fiasco makes short shrift of the text’s excessive formalities—the number of knights are cut from six to three. Instead, this production unleashes the cut-ups that are King Simonides (original Fiasco member Andy Grotelueschen) and his daughter, Thaisa (Founding co-Artistic Diretor Austrian). Grotelueschen, a 2019 Tony nominee for playing Jeff Slater in the Broadway production of Tootsie: The Musical, was born to play Simonides. A student of clowning as an art form, he tackles the role with infectious manic energy and throw-what-you-got-and-see-what-sticks courage, along with incisive comic line readings. Austrian is a perfect foil playing his daughter. They snap at each other like hissing cats, which is their way of expressing their deep love for each other. It’s not just love we see but fun, too, a family embracing joy and life. I usually see Pericles portrayed in this scene as overly shy and withdrawn, but this production’s foundational principle for staging this passage is Pericles describing Simonides as like to his father; thus, Wechsler's Pericles ends up fitting into the family dynamics while the other knights maintain their lofty formality.

Exemplary of Fiasco's cunning staging capabilities is the visual path they create for Thaisa’s letter to her father stating her desire for Pericles. In the text, Simonides reads the letter he receives offstage, then, as part of a practical joke, shows Pericles the letter as evidence of the Tyreen's treason. In this staging, we see Austrian write the letter while singing a duet with Pericles in separate bedrooms. She hands the letter to her father. He reads it, approves her choice but not her willful tone, which we've already seen is the source of their constant bickering. Simonides accosts Pericles, hands him the letter, and accuses him of treason. What happens next is not textual but is natural: Pericles shows Thaisa her letter. Austrian unleashes a full-throttle scream while darting eye arrows furiously toward her father for revealing her letter. Whereupon that father springs the punchline, ruling that henceforth they shall be man and wife. As Pericles looks befuddle at Simonides, Thaisa starts laughing in gales: you got me this time, dad.

As Pericles and a very pregnant Thaisa set sail for Tyre, a large blue sheet creates a ship’s bow in which the couple have a Titanic moment (absent the king-of-the-world outstretched arms). The sheet turns into another sea-storm wave, and with another chime, Pericles emerges from the fabric in the person of Brody.

In Shakespeare's text, we are with Pericles on deck as, belowdeck, Thaisa appears to die giving birth to their daughter before her nurse, Lychorida, appears with the baby. This production reverses this perspective, yielding more emotional power: we stay with the laboring Thaisa and attending Lychorida (Young) on the stage and see Pericles up on the deck through the background sheet, piloting the ship to safety. Pericles comes down, learns his wife’s fate, and takes the baby he names Marina from Lychorida. Taking his next line, "Now, mild may be thy life!" for instruction, Brody turns the ensuing remorseful verses into a soothing lullaby for the babe before placing the infant on Thaisa’s breast.

With the yet-living Thaisa turning to a vestel's life in Ephesus and Pericles back in Tyre, the play turns its focus on the now-teen Marina (Young) whom Pericles left with Cleon and Dionyza to raise in Tarsus. I've seen Young in five Fiasco productions, and her performances never fail to leave me awestruck. In Pericles, those performances include an incestual princess speaking one line, one of three unnamed fishermen, and Lychorida sharing the stage with a dying mother and grieving father. Now, her Marina becomes a dominant force theatrically as well as narratively through to the play’s end.

Marina has grown up to be an object of envy for Dionyza, who plots to have her murdered. In an unusual textual shift, the scene in which Dionyzia and Cleon discuss a murder already done has been moved up to before Dionyzia’s attempt to do the murder. This shift was likely due to logistical purposes (there's more parts to Pericles to be played), but it also boosts the narrative. Now, instead of bemoaning a murder done that he had no part in, Cleon is complicit in Dionyzia's plot because he didn't prevent it, earning the ultimate fate handed to both he and his wife for their unthankfulness.

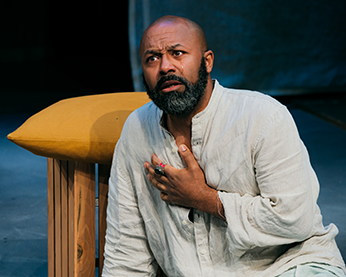

Four actors play Pericles in the Fiasco Theater's production of Shakespeare's Pericles at the Classic Stage Company in New York. From top, Paco Tolson gets caught up in a wave during a storm; Tatiana Wechsler, right, dances with Thaisa (Jessie Austrian); Noah Brody mans the ship's rigging during a second storm; Devin E. Haqq reailzes the maid meeting him in Mytaline really is his daughter, Marina. Photos by Austin Ruffer.

Four actors play Pericles in the Fiasco Theater's production of Shakespeare's Pericles at the Classic Stage Company in New York. From top, Paco Tolson gets caught up in a wave during a storm; Tatiana Wechsler, right, dances with Thaisa (Jessie Austrian); Noah Brody mans the ship's rigging during a second storm; Devin E. Haqq reailzes the maid meeting him in Mytaline really is his daughter, Marina. Photos by Austin Ruffer.

Before Marina can be murdered, pirates kidnap her, one of them (Grotelueschen) shouting “I have got the flowers!” (not in the text) before running off stage. Born to play Simonides and a pirate, next up for Grotelueschen is a pimp, Boult, in the Mytilene brothel that purchases Miranda from the pirates. Teamed with Austrian playing the Bawd, the two grow increasingly flustered by the unattaintable Miranda, who not only doesn’t give up her virginity, she converts the customers. As Boult is about to unvirgin Marina himself, she tries to convert him. He digs in with this response: “What would you have me do? Go to the wars? Where a man may serve seven years for the loss of a leg, and have not money enough in the end to buy him a wooden one?” Grotelueschen’s urgent tone resonantly echoes Shakespeare’s depiction of society’s regard for war-impacted individuals expressed by ruffians and princes alike across the canon. This seems to move Young’s Marina, who gives him the gold Mytilene’s governor had just given her and convinces Boult to pimp her to wealthy families as an arts and crafts teacher instead of a prostitute.

About that governor, Lysimachus: Tolson’s portrayal represents how Fiasco’s studiousness and talents converge to tackle great conundrums in the canon—in this case, how do you requite the man Marina eventually will marry with the man who arrives at the brothel? Do you play him as a hypocritic lady’s man or as a hypocritic governor? Or do you let Shakespeare show you the tools you need to clarify this character?

The clarification starts with the scene before, when two gentlemen leave the brothel after Marina converts them to the equivalent of Christianity. “I am for no more bawdy-houses: shall's go hear the vestals sing?” says one. “I'll do anything now that is virtuous; but I am out of the road of rutting forever,” replies his fellow. In every production I’ve seen, this scene is a throw-away or goes by so fast it gets nary a laugh. Fiasco slows it down to make clear the two gentlemen have gone through a profound transformation. Bringing about that transformation was the preaching of the virgin they intended to ply.

With this evidence as background, Tolson leaves no doubt about his Lysimachus’ character arriving at the brothel in an elaborate disguise. He engages with the whorehouse staff—who already knew it was him but pretend to be surprised—with comfortable bonhomie. He doesn't want to undermine his rule, but he does want good sex, and he wants that with quality women, assurance he seeks not only from the Pandar but from the woman herself. He interrogates Marina before they get down to business; it's just not the business he was expecting. Young’s Marina is not the ever-so-sweet girl I’ve usually seen but a woman with a powerful edge sharpened by a simple sense of logic to go with her strong sense of morality. It’s logic that drives her vehement retorts to Lysimachus, and seeing her power in her presence and in her mind, the governor nervously gives her gold, and then a second purse. While taking his anger out on the pimps for allowing himself to be put in that situation, he champions Marina’s virtues. Conversion complete, but more depth to the character is yet to emerge.

For Pericles has arrived in Mytilene as a new, albeit, broken man. Visiting the memorial Cleon and Dionyza erected to the allegedly dead Marina, the chime sounds again, and Haqq (who had been playing Cleon) replaces Brody as Pericles. Having lost his wife and daughter, Pericles falls into a state of depression so severe he will not do anything or communicate with anybody. When his ship ends up in Mytilene’s bay, Lysimachus goes aboard to welcome the Tyreens. Learning from Helicanus about Pericles’s condition. Lysimachus, rather than a ubiquitous First Lord, thinks of Marina and directly calls to her to tend to Pericles. Though in service to the small cast, this staging suggests that Lysimachus brought Marina with him to visit whoever is on this "goodly vessel.” Furthermore, nothing in the text suggests he only considered marrying Marina after learning she was a princess. That may make good comedy, but “I have another suit,” is all he says about the matter, and Pericles immediately guesses: “You shall prevail, were it to woo my daughter; for it seems you have been noble towards her.” An obvious respectful relationship already exists between governor and the never-would-be prostitute. Besides, the play already has set a precedence for the Mytilene governor: King Simonides was more than happy to marry his princess daughter to a mere “gentleman of Tyre” before learning Pericles was of royal lineage.

The reunion of Pericles and Mirana is so expertly written, it’s hard to not play it without inducing tears. Young and Haqq achieve a particularly deep level of emotional rawness. “Thou dost look like Patience gazing on kings' graves, and smiling extremity out of act,” Pericles observes of her, a description that nails Young’s performance. Haqq, meanwhile, superbly portrays a father hearing Marina’s tale, so wanting to believe this is his daughter, but unable to—afraid to—reconcile what she’s saying with the truth he thinks he knows, that his daughter is dead. It takes Marina’s grace along with her faith to pull him slowly out of the deep pit of his depression.

The four-actor Pericles can be confusing at first, but well-crafted acting and execution of the conceptual staging solves that before the second transition. After his reunion with Marina comes Pericles's vision directing him to Diana’s temple in Ephesus, where he will unexpectedly reunite with Thaisa, too. As the cast provides the “music of the spheres” with a refrain “To guide me home,” the three previous Pericles present their characters’ key accoutrements to Haqq's sleeping Pericles: the blue sash Tolson wore when courting Antioch’s daughter, the armor breast plate that Wechsler wore to the tournament for Thaisa, the just-born babe that Brody placed on the breast of his assumed dead wife.

Pericles is whole at last—once he gets his wife back.

Eric Minton

March 27, 2024

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances