Timon of Athens

The Ultimate Unraveling of Status and Image

The Philadelphia Artists' Collective, Broad Street Ministry, Philadelphia, Pa.

Friday, April 5, 2013, Center second row in box theater

Directed by Dan Hodge

In Timon of Athens, Shakespeare rails at hypocrisy and casts as tragedy a beneficent man who allows himself to fall victim to it. Timon obliviously spends to excess, and much of his spending is on extravagant gifts for his friends. Soon his coffers are empty and his debts too deep; he is a toxic asset. When his steward, Flavius, finally convinces him of the state of his finances, Timon confidently sends Flavius and his other servants to seek financial assistance from those lords and senators who have most enjoyed his beneficence. All turn him down, and Shakespeare gives us three scenes in which their denial comes off as so transparently hypocritical as to be intentionally comic.

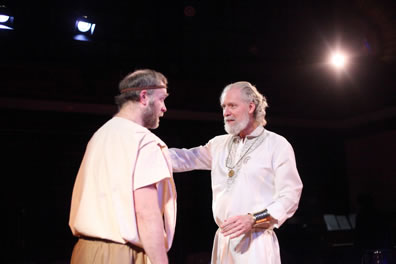

Timon (Christopher Coucill) assures his steward, Flavius (Nathan Foley) that though his coffers are currently poor, he is still rich in friends who will give him financial assistance—not— in the Philadelphia Artitsts' Collective production of Timon of Athens. Photo by Kate Raines, Philadelphia Artists' Collective.

But the last of these three scenes gets an important twist in the production put on by the Philadelphia Artists' Collective (PAC). That third lord, Sempronius (Felicia Leicht), first suggests that Timon turn to his other friends, but upon learning that he already has hit up the others, she expresses indignation that she is the last consulted. "It shows but little love or judgment in him … he's much disgraced me in't." She notes that if she were to rescue him after all the others denied him, the other lords would consider her a fool. "Who bates mine honor shall not know my coin," she says angrily and storms off stage. Nothing comical in this Sempronius; rather, her self-absorption is typical of the society depicted in this production where status and image matters more than friendship, loyalty, or financial security.

Sound familiar?

Director Dan Hodge dresses his Timon in Greek-themed costumes, but even so I felt I was watching a modern drama playing out in Washington, Los Angeles, or New York rather than the intimate space of a church's small fellowship hall. Everyone in this play is image conscience. Timon's excessive beneficence grows out of his hunger to be loved—he wallows in praise. Christopher Coucill plays Timon with pervasive kindness, but he looks at the receivers of his gifts in eager anticipation of their appreciation, his eyes pushing them to lay upon him their gratitude. Alcibides (Jihad Milhem), the Athenian general, uses trumpets and drums to announce his arrivals, and he wears his military pride in his bearing and humble-honored expressions. Later, in what he thinks is the privacy of the woods, he enjoys a ménage à trois with a female and male whore. Even Apemantus, the bitter cynic (a woman in this production) who serves as the play's conscience commentator—a blending of a Shakespeare's fools with As You Like It's Jacques—promotes herself as a disdainful and disdained thorn in society's side, lapping up scorn as much as Timon does praise. But when Timon later calls her "slave," the accompanying action shows the word to be more than a pejorative exclamation but a statement of fact, and Apemantus is ashamed to be reminded of her real status.

Class is an ever-present aspect of this production, with three clearly defined tiers of Athenian society. Timon, the other lords, and the senators are at the top, and they maintain their aspects with nose-uptilted regard. Flavius and the other servants (slaves here) are at the bottom, and they keep their heads down and manners reserved, curtsying on cue. The Poet, Painter, and soldiers (even Alcibides) exist in between, striving for a place at the table and barely tolerated by the upper class. That the Poet and Painter get to eat at the great banquet, and Alcibides is the guest of honor is evidence of Timon's charity in this production.

Thus, in the scene of Alcibides' banishment, to the senators his crime is insolence, not simply his persistent urging of pardon for his soldier who killed a man in a brawl. "My lords, I do beseech you know me," Alcibides implores. "Call me to your remembrances… my wounds ache at you." "Do you dare our anger?" replies the First Senator (Annette Kaplafka), and a line later she banishes Alcibides. Never mind that this general has been Athens' protector par excellence, his request for respect is intolerable to the senators.

This link of politics and social standing comes to the fore with the second of the three lords to turn Timon down. That lord, Lucius (David Blatt), is also a senator in this production, and his scene opens with him crying shame that other friends have denied Timon. "For my own part, I must needs confess I have received some small kindnesses from him, as money, plate, jewels, and suchlike trifles … yet had he not mistook him and sent to me, I should ne'er have denied his occasion so many talents." Just then, the steward does come to Lucius asking for 5,500 talents, and Lucius claims that he had just the day before invested all his ready cash in another purchase. "Tell him this from me," Lucius orders the steward to relay to Timon: "I count it one of my greatest afflictions, say, that I cannot pleasure such an honorable gentlemen. Good Flavius, will you befriend me so far as to use mine own words to him?" That those very words are disingenuous—spin—is the scene's point here, not merely Lucius' ingratitude or hypocrisy.

Denied by his fellow lords and the senate, Timon literally strips to nakedness and turns his back on Athens, seeking to live like a beast in the woods. Coucill makes the transition from grandfatherly kindness to a madman misanthrope convincingly, and the second half of the play is set outside his cave in the woods. These scenes are played to more laughs than was the hypocrisy of the play's first half. When Coucill's Timon finds a horde of gold instead of the roots he's digging for, his incredulity is priceless. Scene by scene he encounters various Athenians. Alcibides and his whores are the first to come upon him as the general is marching on Athens, and Timon gives them gold to be rid of their presence. Thieves who come to steal the gold are so disgusted with Timon's attitude of hatred toward mankind that they refuse to even accept the gold he gives them. The Poet and Painter hope to return to his good graces, and in their fawning they fall into his trap to reveal them for the sycophants they really are.

Flavius, the loyal steward, unaware of the gold Timon has found, also comes to offer his continuing service. Nathan Foley plucks our heartstrings in his portrayal of Flavius. In the early scenes, we can see the consternation in his face, knowing Timon's true financial condition while his master continues throwing money and gifts about, but he is bound by status to hold his tongue. How do you adequately serve your master when he insists on being gullible? In the woods, Flavius arrives with a blanket, some food, and the few coins he has left, all of which he offers Timon. This cracks Timon's hatred. "Thou singly honest man," he says, and he gives Flavius gold to start a new life (he also removes from Flavius the headband identifying him as a slave). Shakespeare has Timon retreat to his cave after this, and Flavius exits "another way," but Hodge has the steward linger on the stage when Timon goes to sleep in his cave. Foley's Flavius doesn't know any life beyond loyalty to his master, so he returns the gold to the box, places his own coins and food next to the sleeping Timon and lays the blanket over him, then sits and waits, staring into confusion as the lights go down and the play moves on to the next scene.

Ironically, Apemantus believes herself to be the play's "singly honest man" and Timon's one true friend, having never taken advantage of his kindness and prophesying what would befall him. Whens she comes to succor and embrace Timon, he regards her as just another image-conscience Athenian—"Thou flatter'st misery," he tells her—and this sets her off. Charlotte Northeast plays the part with such persistent vigor she adds an electric charge to an otherwise sluggish production, and her interactions with Coucill's Timon sparkle. The two end up waging a full-volume argument that degenerates into one-word insults. "Away, thou issue of a mangy dog!" Timon yells at Apemantus as he out-cynics Apemantus. She nevertheless establishes her superiority, in her mind, by pointing out that Timon comes to his cynicism through personal loss whereas she arrived at hers through studied philosophy.

The Athenian general Alcibides (Jihad Milhem) pleads for the life of a soldier on trial for murder before the Athens Senate. In the background, Senator Lucius (David Blatt) and the First Senator (Annette Kaplafka) listen in a scene that leads up to Alcibides' exile. Photo by Kate Raines, Philadelphia Artists' Collective.

Apemantus also points out not only Timon's pathological fault but the problem plaguing Shakespeare's composition of this play: "The middle of humanity thou never knewest, but the extremity of both ends." Timon of Athens is a flawed composition, either a poorly carried out collaboration (many scholars believe) or an unfinished manuscript (my belief: it reads like first draft that needed one more read-through from Shakespeare to excise the superfluous portions, tidy up the plot's loose ends, and tighten the allegorical arcs). No evidence exists that it was performed in Shakespeare's time, and frankly the play, as published in the First Folio, is largely unperformable in our time. The PAC's cut of the play is superbly rendered, providing a smooth story line, logical progression of scenes, and well-defined, easily discernable characters.

So, when the two senators come to beg Timon to return to Athens and help the city withstand Alcibides' invasion, we recognize them as the snobs who banished Alcibides and denied Timon in the first place. What chutzpa! But these senators don't see it that way; they appeal to Timon's sense of duty and humanity, disregarding—or oblivious, perhaps—to their own lack of duty and regard for fellow citizens that brought on the city's predicament in the first place. When Timon offers only a tree from which every Athenian can hang themselves, the senators return to the doomed Athens.

Certainly, this production could have been performed in modern dress. However, using vaguely ancient Athenian costuming has a way of condensing time from then to now and so brings home both the timeless and timely lessons of the play. The Athens in this play fell as did the Athens of ancient reality. The great Roman Empire fell, the Great Britain empire (a fledgling one in Shakespeare's time) fell, and more recently the regimes in Egypt and Libya fell and Syria's government hangs in the balance. The common condition: self-serving leaders creating top-heavy societies rather than shoring up the crumbling foundations of social classes below them.

This doesn't sound too familiar, I hope.

Eric Minton

April 10, 2013

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances