Twelfth Night

What Achieved Greatness Was Born Great

Opus Arte/Shakespeare's Globe (2013)

Directed by Tim Carroll, with Mark Rylance, Stephen Fry, Roger Lloyd Pack, Paul Chahidi, Colin Hurley, Johnny Flynn, Samuel Barnett, Liam Brennan.

If there's any fault with the DVD version of Shakespeare Globe's 2012 production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night it is this: the production improved after it was filmed. By the time this production reached Broadway last winter, the performances were keener, the ensemble tighter, and the action funnier.

If there's any fault with the DVD version of Shakespeare Globe's 2012 production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night it is this: the production improved after it was filmed. By the time this production reached Broadway last winter, the performances were keener, the ensemble tighter, and the action funnier.

So, for those of us who saw the Mark Rylance–led performances at New York's Belasco Theatre this DVD jogs a fine memory and makes a better memento than, say, a playbill or t-shirt. For everybody else, it's an opportunity to see this landmark, original practice, all-male-cast production of Shakespeare's most polished comedy.

First mounted by Shakespeare's Globe in 2002 when Rylance was serving as the theater's artistic director, this Carroll-helmed Twelfth Night was revived for the Globe's 2012 season with Rylance reprising his role as Olivia, Paul Chahidi returning as Maria, Peter Hamilton Dyer as Feste, and Liam Brennan as Orsino, while Colin Hurley graduated from Antonio to Sir Toby Belch. Whether it was these actors' return to these roles 10 years on or the additions of Stephen Fry as Malvolio, Samuel Barnett as Sebastian, and Roger Lloyd Pack as Aguecheek, the 2012 version achieved stratospheric status among critics and audiences. After its successful tenure at the Globe, it moved to London's West End for a sold-out run which prompted its New York residency a year later where it became one of Broadway's biggest hits and earned seven Tony nominations: Best Revival of a Play, Direction (Tim Carroll), Costume Design (Jenny Tiramani), and cast members Rylance, Barnett (as Viola), Chahidi, and Fry.

Many might argue that its box office success was due to Rylance's star value or the gimmick of seeing either original practice Shakespeare or a drag show, take your pick of term. The fact that the actors got into makeup and costume on stage as the audience entered the theater probably enticed some customers, and even the music played on Elizabethan instruments could have a been a draw for a few. But make no mistake, many other productions have their gimmicks and star status (as Twelfth Night's Broadway run was beginning, Orlando Bloom was motorcycling on stage as Romeo in half-filled houses down the street). It was Shakespeare himself and great actors nailing their Shakespeare-written portrayals that generated the production's word-of-mouth success on both sides of the Atlantic. Gimmickry does not net Tony nominations, including three out of five nods for featured role in a play (Barnett's nomination is for leading role, where he's up against Bryan Cranston in All the Way, Chris O'Dowd in Of Mice and Men, Tony Shalhoub in Act One, and Rylance as Richard III).

The evidence is all on this DVD. Let's start with Carroll's direction. Yes, indulging in original practice dictates, in this instance, men playing the women and authenticity from the live music to Tiramani's costumes constructed with fabric replicating that of the 1590s. But it also means the performances hew strictly to the text (though the actors don't use original pronunciation). What comic flourishes the actors provide arise out of their characters, and laughs are earned by the lines and situations instead of extraneous stage business.

What is most refreshing about such text-centric rendering is that some of the characters, unencumbered by 400 years of portrayal traditions, emerge into whole new lights. This is especially true of Fry's Malvolio. He is no villain; he is no obnoxious clown. He is, merely, "a kind of puritan," serious, self-centered, holier-than-thou even to his lady, yes, but quite a good administrator of her household, too. His tragic flaw is not any of these qualities; rather, it is his fantasizing the possibility that his lady might love him. I have never before seen a Malvolio I've so identified with. Consider that his acted-out fantasy in the garden is no different than you or me daydreaming. How would you like your fantasies exposed and used for humiliation and imprisonment?

And all simply as retribution for doing your job and stating an opinion asked of you by your boss."What think you of this fool, Malvolio? Doth he not mend?" Olivia asks. Note the first word of Malvolio's answer: "Yes, and shall do till the pangs of death shake him." He could have said, "No," and suggested Feste still be tossed out on the streets. Yet, Feste still insults Malvolio, and only then does the steward rebuke him, and when he does, Olivia checks him for it. That should have been the end of it, but Feste is the one who harbors the grudge. In the night revelry scene, Maria warns the three partiers that Olivia probably had already employed Malvolio to turn them out of doors. When Malvolio does appear, Fry delivers his opening lines—"My masters, are you mad? Or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night?"—matter-of-factly, not indignantly or arrogantly. "Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time in you?" is a legitimate question; cops are called to neighbors' homes for no less a loud carousing than Toby, Aguecheek, and Feste are perpetrating in this house of mourning (and Maria is entirely aware of this fact, too). Toby offers a drunken pun in return and with "Sneck up!" reminds Malvolio he should remove his cap in the company of nobility, which Malvolio does. Fry speaks Malvolio's next line with great care in his choice of words: "Sir Toby, I must be round with you. My lady bade me tell you that though she harbors you as her kinsman, she's nothing allied to your disorders." The Olivia we see in her first scene would certainly tell Malvolio such a thing, and Maria's earlier warning is further confirmation.

None of this diminishes the comic value of the box tree scene (played with a tree that is literally a box). Fry's portrayal is so simply honest that his Malvolio slips ever deeper into the trap the more he is overcome with confirmation that his great wish is being fulfilled. "I do not now fool myself, to let imagination jade me; for every reason excites to this, that my lady loves me," a line Fry ends with such incredulous wonder that you can hear sympathy in the audience. "I am happy," he says with innocent wonder. This is funny, and this is sad, too, and the audience just melts for him. If you know what's coming, your own heart will ache.

As Malvolio is clearly not a villain, Toby Belch becomes something of a villain. On Broadway, Hurley had rounded the character into a genial yet mischievous jokester, but in the DVD version his Toby has a much sharper edge. With a Bardolph nose and cheeks of flaming red, this Toby is the kind of loudmouth drunk we laugh at as long as he's in the next section, but once he comes into our vicinity, we see him as a real annoyance and more dangerous that funny. Even Hurley himself seems to realize this about the knight, for he has found snatches of lines and moments of pause that he uses to display a Toby who recognizes how incorrigibly drunk he's become.

Dyer's Feste keeps his psychological distance, if not a physical separation, from Toby. It is Fabian (played with slick slyness by James Garnon) who serves as Toby's cohort in mischief. Pack's Aguecheek, on the other hand, is an elderly gull, ever delusional about everything he thinks himself to be: a dancer, fashion monger, converser, swearer, fighter, courtier. Pack's measured pace is in contrast to Hurley's uninhibited energy, and much of Aguecheek's humor grows in this gap between the two, thanks to Pack's timing. (Angus Wright took over the part in New York, providing a slightly more frenetic reading but with a faux regality that made him an endearing character.) Pack's meltdown during the faux fencing scene with Viola is preciously done.

So, what does Maria see in this Toby? Redemption—his, and perhaps hers. Chahidi's performance on the DVD is as appreciable as it was on Broadway. He is all woman, prim but yet a proper tease balancing her sense of formal duty to Olivia with her adoration of Toby. Her switching places with Olivia for Viola's first embassy leads to a great comic moment as Viola begins her speech with "Most radiant, exquisite, and unmatchable beauty," then realizes that the woman at the head of table is nothing of the sort—especially when Chahidi offers a crooked smile. This Maria's loathing of Malvolio comes off as jealousy rather than reaction to abuse; Olivia clearly has greater regard for and gives higher rank to the steward than for the waiting woman. In this staging, Maria works out her plot against Malvolio as she speaks her lines. "I can write very like my lady your niece," Chahidi's Maria says as the thought just then occurs to her, then looks at Toby as dawning glee comes over both. "On a forgotten matter we can hardly make distinction of our hands," Chahidi's Maria continues, growing in excitement. "Excellent! I smell a device," Toby exclaims.

As with Chahidi's Maria, Rylance's Olivia is marvelous in its own right but more so for the memory of his New York performance. It starts with that walk. Wearing a matronly, floor-length, black dress of mourning, Rylance moves with such tiny steps and stiff formality he seems to glide like a wound-up porcelain doll on wheels. The first time he crosses the stage, the audience laughs, and everything about his movements and expressions is so painfully reserved it's hilariously funny. That sets up the comic strand that comes with Viola's first visit, and Rylance ingeniously piles up the laughs as his very formal, very serious, and very proper Olivia comes undone.

Brennan's Orsino is, literally in physical appearance, sick in love, wearing what looks like a bed gown and nightcap. His performance seems overly demonstrative at first, speaking his lines as grand rhetoric. But it turns out that this Orsino is enamored of music and poetry, and he gets caught up in song and allegory like an opera aficionado does with a Pavarotti-sung aria. However, as the play progresses and Orsino becomes obviously confused by his feelings for Cesario, we see the reason Brennan was brought back for this revival and kept on when it transferred to New York, for he acts with such subtlety of movement and inflection, and his increasing bafflement at the end is sublimely played.

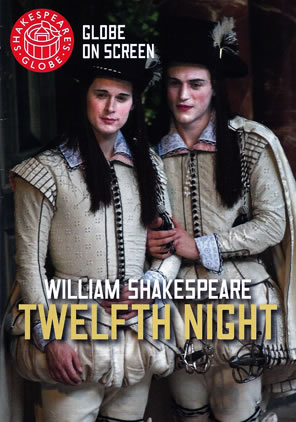

The Opus Arte DVD's liner notes shows Samuel Barnett as Sebastian (left) and Johnny Flynn as Viola.

This production's one blemish—and it is only so relative to the New York staging—is in the casting of Johnny Flynn as Viola. This is not a slam on his acting abilities or performance, for he exhibits Viola's discomfort in her absurd situation with nervous ticks and breaking voice. His best moment comes in the faux fencing scene with Aguecheek where Flynn's physical comic skills are put on display. In Flynn's portrayal, Viola, in her first scene as Cesario, doesn't know how to even wear a sword, and this becomes a running joke culminating in his fumbling to get the sword out of its scabbard as the fight approaches. However, he is cast opposite of Barnett as Sebastian. Flynn is taller, and even in playing Viola in her "woman's weeds" he looks and moves too masculine. You thus don't feel the confusion on the scale as we did in New York when Barnett shifted to Viola and near look-alike newcomer Joseph Timms took on Sebastian.

Meanwhile, Barnett here creates an indelible impression as Sebastian, turning the play's other twin into a foundational figure. When he switched to Viola for the New York run, though his physical style was less broad than Flynn's is here, Barnett's precision and ability to layer every one of Viola's warring emotions into a single expression raised his portrayal to one of true greatness. That precision and expressiveness is here in his Sebastian, too.

One other Globe performance that transferred to New York is that of John Paul Connolly as Antonio. I have little recollection of him in the Broadway version, but on this DVD he presents what might well be a definitive portrayal of this minor role. Sticking to the text, Connolly gives Antonio no homosexual nor fatherly overtones. When he learns Sebastian's true identity, he suddenly realizes he is in the company of nobility (the classes are clearly demarcated in this production), and this is all the motive he needs for following the young man. Connolly's Antonio is a man of action and honor who sees danger as sport and obviously means what he says when he tells Sebastian that he followed him to Orsino's court "Not all love to see you … but jealousy what might befall your travel, being skill-less in these parts, which to a stranger, unguided and unfriended, often prove rough and unhospitable." Such a sense of courtesy charges this Antonio's passion when the boy he thinks is Sebastian denies him. And it is Antonio who keys the Act Five reconnections, and Connolly carries out that duty perfectly.

This is a historical Twelfth Night. It's one of those stage productions that will be talked about for ages, as with the Orson Welles Julius Caesar, the Laurence Olivier Richard III, the Richard Burton Hamlet, the Peter Brook Midsummer Night's Dream, the Ian McKellen–Judi Dench Macbeth, the Judi Dench–Anthony Hopkins Antony and Cleopatra, and the Al Pacino Merchant of Venice. This is the Mark Rylance Twelfth Night, and unlike many of the other above-mentioned productions, the original stage production is captured on film (the McKellen–Dench Macbeth is the only other; the movie version of Olivier's Richard was inspired by but not the same as his theatrical production). As such this DVD is a must for your collection, and more so if you like your Shakespeare truly pure.

Eric Minton

May 22, 2014

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances