Twelfth Night

Some Achieve Greatness

Folger Theatre, Washington, D.C.

Sunday, May 5, 2013, G-1&2 (center stalls)

Directed by Robert Richmond

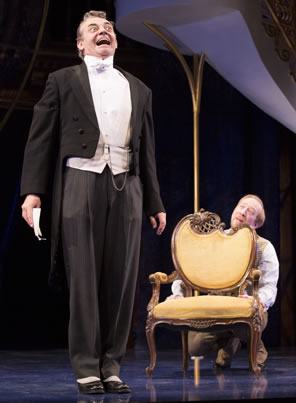

Malvolio (Richard Sheridan Willis) learns how to smile as Aguecheek (James Konicek) watches in the Folger Theatre's Twelfth Night. Photo by Scott Suchman, Folger Theatre.

In terms of playwriting, William Shakespeare may have reached his zenith with Twelfth Night. The main plot is suspenseful fun, the subplot slides in and out smoothly, and what a cast of characters! It may be Viola's play, but top-billed actresses have variously played her, Olivia, or Maria, while actors have done star turns as Malvolio, Sir Toby Belch, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, and Feste. I've even seen show-stealing portrayals of Orsino, Antonio, Sebastian, and Fabian (afterthought character though he may be). Indeed, every part in this ensemble piece is a fully fleshed, individualized creation except maybe the Priest, and even his eight lines earn appreciative applause when Joshua Morgan chants them in this Folger Theatre production.

Still, even Shakespeare at his best is not good enough for director Robert Richmond. As he does with every Shakespeare play we've seen him helm for The Folger, he has to fiddle with scenes, cut key moments, and remold characters in addition to shaping the action to his conceptual setting. Some of these decisions create fault lines in this production. However, Richmond also has a knack for assembling superb ensembles and allowing his actors to soar to scintillating states of singularity with their characters. Most importantly, he keeps Twelfth Night a comedy, and this production scores many laughs and lively fun along with some enlightening Shakespearean moments.

Richmond, seeking an appropriate Illyria in time and place for today's audience, settles on the early 20th century, and he pegs the action to the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. In costume (designed by Mariah Hale) and in scenic design (by Tony Cisek, who has erected a giant Tiffany-like stained-glass disc hanging over a third of the stage and a spiraling gold-trimmed staircase to one side), this Twelfth Night has a Downton Abbey-cum-Titanic look and feel. Subconsciously, we are in the time of nevermore, the dreamlike days of Daisy and her bicycle built for two.

This setting also brings attention to the class distinctions Shakespeare toys with in Twelfth Night. This is an ordered society, with clear demarcations between the upstairs world of Olivia and Orsino (and the twins, Viola and Sebastian in their original state) and the downstairs world of Maria, Malvolio, and Cesario (the disguised Viola). Sub-stratifications mean Maria must curtsey to Malvolio. "Be not amazed; right noble is his blood," Orsino tells Olivia, referring to Sebastian, as if to assure her she's not marrying below her station. Of course, she originally thought she was marrying well below her station when she wooed Cesario, and was more than willing to do so. Toby and Maria also fudge these stratifications while Malvolio sees himself readily overleaping them. Antonio (Chris Genebach in a portrayal of unceasing virility) at first seems eager to be a servant for the Sebastian he rescued—service was an honorable occupation in those days and appears to be a step-up for this Antonio; however, in subsequent scenes, Genebach falls back to the now-standard portrayal of Antonio as a gay man crushing on Sebastian.

Richmond opens his production with the twins apparently on a cruise ship and dressing together in identical men's clothing for some social event, a superfluous exposition that Trevor Nunn also used in his film version of Twelfth Night. After the ship's sinking, Sebastian and Viola (William Vaughan and Emily Trask, respectively) dance in long strands of fabric as if drowning, a device Taffety Punk used in its production of the play earlier this year. As with the Punk production, this one's opening line is Viola's "What country, friend, is this?" spoken to Feste instead of the sea captain. Richmond then starts shufling his scenes together. We get the Captain's, er, Feste's expository description of Illyria's gossip interweaving with Shakespeare's opening scene of Orsino ("If music be the food of love, play on") and a manufactured scene of Olivia's household in which Rachel Pickup as the countess speaks the lines that, in Shakespeare's original, Valentine delivers to Orsino.

Twelfth Night is so often produced (this is the 19th stage production I've seen) that I doubt there's any new ideas a director could bring to the play. Yet, I've never seen a Toby Belch like that Craig Wallace delivers. Wallace, as he did with his Gremio in Taming of the Shrew and his Brother in Much Ado About Nothing, both also at the Folger, has a way of coming up with the freshest of readings when he plays a Shakespeare character. I feel like I am hearing Toby's lines for the first time, so unique are his takes on them. A rascal of a man, his Toby is the carefree carouser of his age, the privileged adventurer unconcerned with Victorian morals (he even seems to be modeling himself after Victoria's son, Prince Edward). Yet he knows his place—it's above Malvolio and Cesario, and even among his peers (Aguecheek) he sees himself as superior in guile if not in intellect. Sir Andrew, in a squealing gadfly of a performance by James Konicek, wants to emulate Toby but he just doesn't have the mental capacity or immoral fortitude to do so. Noticeably, he sneezes whenever a woman is on stage. Allergies, probably.

Wallace presents a key pivotal point in Toby that I've never seen before but, on reflection, seems so right. When Olivia breaks up his fight with Sebastian (whom everyone believes is Cesario), she berates her uncle as "Ungracious wretch, fit for the mountains and the barbarous caves." Wallace's Toby, genuinely upset by this approbation, reaches out to touch his niece's shoulder, whereupon she rounds on him again: "Rudesby, be gone!" A hurt Toby saunters off the stage, and we immediately see a different side of his relationship with Olivia. She's a favorite niece, perhaps, whom he's come to aid in her time of loss (father and brother in less than a year), a woman he genuinely drinks healths to, albeit a few too many. This reproach from Olivia comes before the prison scene with Malvolio, and it gives greater weight to Toby's remark, "I am now so far in offence with my niece that I cannot pursue with any safety this sport to the upshot."

In this speech, Toby is giving instruction to Feste, and he ends it with, "Come by and by to my chamber." Wallace, though, clearly directs this last line to Maria. Tonya Beckman's Maria is so elated she can hardly contain herself, for she is and always has been, it seems, dotingly in love with Toby. Beckman plays Maria with bubbly bawdiness and a genuine love for life; a kindred spirit to Toby.

And, lord! how she cannot stand Malvolio. As astonished as I was by Wallace's Toby, Richard Sheridan Willis as Malvolio topped any I've ever seen. Not just pompous but religiously so, this self-centered steward maintains his ramrod dignity even when, after being punked, he comes in smiling and looking like a bumble bee in a 1900-style swimsuit with codpiece and garters crossing from the yellow and black stocking on one leg to the pants bottom on the other leg. A pearl necklace completes the effect. In the letter-reading scene, Richmond cuts many of the asides by Toby, Aguecheek, and Feste (replacing Fabian, who has been totally excised in this production). This choice does not diminish the scene's comedy, for all the laughs are focused on Willis's reading of the letter, and when he pauses to figure out the M.O.A.I. anagram, the other three hiding behind chair, column, and stairs inch forward urging, urging, urging him to figure it out. An even bigger laugh is accomplished with his leaving the stage (through the audience) after reading the first half of the letter, then returning (and scattering the conspirators, who have come out of hiding) with a shout of "Here is yet a postscript!" That postscript commands him to smile, and Willis's Malvolio urges, urges, urges a smile to break through the cement of his stern countenance. This is as good a gulling scene as you will see anywhere.

Malvolio's prison is the piano, an ornately gold-trimmed grand to one side of the stage where Morgan, when he's not playing minor characters like the priest and officer, plays tunes to accompany the action (he's using an electronic keyboard, for the piano body must hold Malvolio). Willis not only lies cramped in the piano while talking with Feste/Sir Topaz, he stays in that prison through the intervening scenes till his release in the final act. His being there doesn't distract, though, because the action is so enchanting, from the foolish fencing match between Aguecheek and Cesario (Viola gains her confidence as she scores points on the knight) to the more earnest duels between Toby and Antonio and then Sebastian, and, finally to Olivia's snaring Sebastian, whom she thinks is Cesario, and the finale's sweet reconciliations.

Rachel Pickup's Olivia is a scared, tremulous young lady definitely shaken by the double doses of death she's endured. She emerges from that cocoon with the coming of Viola. It's not just that she changes from mourning clothes to a vibrant blouse and dress, her whole demeanor becomes outgoing, bold, and warm. By the time Sebastian comes on the scene, Pickup's Olivia is a woman he could easily fall head-over-heels for in an instant. Emily Trask is much more contained in her portrayal of Viola. She gets a bit rambunctious when she's doing the willow cabin speech, she downright crows "I am the man" when she realizes Olivia has fallen for her, she grows impatient with Orsino when he refuses to credit women with the capacity to love as much as he, and she becomes cocky when she's besting Aguecheek at fencing. All this, though, is in contrast to her otherwise stiff reserve as Cesario. But Trask gets the tear ducts flowing in that last act when Sebastian says, "I had a sister," and Trask's Viola nods just ever so slightly, a gesture that perfectly captures a woman whose long-lost hope has been magically rekindled, but yet she doesn't dare accept that this is her brother in case it really isn't.

The irrepressible Louis Butelli takes on Feste, ukelele in hand, singing Shakespeare's songs as well as classic tunes of the play's era. Ever twirling his bowler hat and dressed in a natty music hall emcee's suit, Butelli plays "an allowed fool" in name only. His delivery of the lines emphasizes their profound wisdom rather than cynical irony.

Sir Andrew Aguecheek (James Konicek, left) fences with Viola disguised as Cesario (Emily Trask) as Feste (Louis Butelli) referees and Sir Toby Belch (Craig Wallace) watches in the Folger Theatre production of Twelfth Night. Photo by Scott Suchman, Folger Theatre.

William Vaughan plays Sebastian as a boy on the verge of manhood, as yet navigating newly experienced emotions while displaying an uncertain cockiness. Describing his sister to Antonio, he says, "A lady, sir, though it was said she much resembled me, was yet of many accounted beautiful," and Vaughan delivers the line with such abashed aplomb that it earns a laugh. Michael Brusasco is an overwrought Orsino at the start, delivering the play's first famous line in an affected lament. This lost-in-love-and-everybody-should-know-it aspect dictates his performance to the final scene when it leads to Orsino becoming a bit too scary as he threatens to murder Olivia and/or Viola. However, Brusasco does such a deftly quick turn when he comes to the describing of Cesario as one "whom I tender dearly"—realizing the moment he says it how dearly he has come to tender this boy—that the would-be monster changes to a hollow fool and comedy quickly fills the vacuum again.

Such surprising moments in this production arise out of what remains of Shakespeare's 400-plus-year-old script. Among other cuts, Richmond's trimming away many transitional lines cause the final scene of sweet reconciliation to lurch along rather than unfold like giftwrap. Meanwhile, he devotes stage time extending transitions from scene to scene with piano-accompanied Keystone Kops–like stage business of characters crossing the stage side to side, back to front, sometimes dancing, sometimes skipping, and often pausing at center stage as if posing for a photo (a motif that starts with Feste taking pictures of the twins before the shipwreck—I know, I don't get it, either). It's forced foolery at the price of whittling away more of Shakespeare's rich fodder that this cast could have turned into a greater gold.

Well, what you will; my takeaway from this overall wonderful experience of a show is an ensemble of brilliant actors who bring Shakespeare's brilliantly drawn ensemble of characters to rarefied heights.

Eric Minton

May 7, 2013

This review also appears on PlayShakespeare.com

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances